But in Kipling country, obedience is a mark of honor. To modern ears, the demand for unquestioning obedience has a primitive and chilling ring-today’s mantra is more likely: question first. Now these are the Laws of the Jungle, and many and mighty are they īut the head and the hoof of the Law and the haunch and the hump is-Obey! The law is a compendium of many smaller laws, but its central and overarching commandment is obedience:

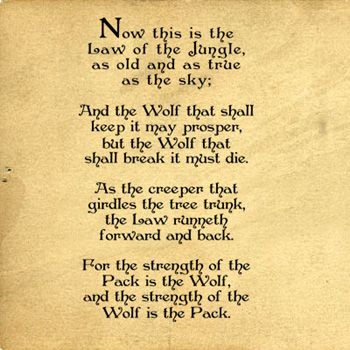

The disciplined members of the wolf pack take pride in calling themselves the “Free People.” (“Wash daily from nose-tip to tail-tip.”) To disobey it is to court ruin for “the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.” To follow the law is not to be servile but to be honorable, as the law is the guarantor of liberty.

LAW OF THE JUNGLE POEM CODE

Its significance is proclaimed at the outset: “The Law of the Jungle-which is by far the oldest law in the world-has arranged for almost every kind of accident that may befall the Jungle People, till now its code is as perfect as time and custom can make it.” Ancient and all-pervasive, it covers every aspect of an animal’s life from hunting to hygiene. Like the “giant creeper” that girdles the tree trunk, the Law runs backward and forward through the Mowgli tales, a paradisiacal saga of a boy who grows up in the jungle with a family of animals. The first is the magnificent and moving Mowgli stories in the two Jungle Books. It is the moving impulse of his writing and never more explicitly engaged with than in two of his celebrated works written in the Victorian high noon of the 1890s when he, too, was at the height of his literary power. He regarded it both as plinth and keystone of the British Empire-and consequently, in his view, human civilization. Few writers have paid fealty to the Law (always in respectful uppercase) more fiercely than this proud imperialist. While his ardor for unsparing retribution has a strong whiff of brimstone-and many of his most famous stories, such as Mary Postgate, have a vengeful sheen-the most striking element of his credo is his adulation of the law, which he treats like some kind of secular god. The granite authority of his beliefs, unsoftened by even the hint of a doubt, is quite astonishing and speaks of a mind that set early. Kipling was a twenty-four-year-old stripling when he wrote that letter, but he sounds like an old martinet. You have got from me what no living soul has ever done before.” He believed in “God the Father Almighty,” he wrote back with asperity, but also “in justification by work rather than faith, and most assuredly I believe in retribution both here and hereafter for wrongdoing, and I believe in a reward, here and hereafter for obedience to the law.” In a parting flounce, he added: “There. As it happened, Kipling was the grandson of Methodist preachers but far from an orthodox churchgoer. But his readers are in her debt, for her question triggered a rare burst of candor from the fiercely private writer. Kipling probably found the inquiry tasteless, and it no doubt helped cool whatever residual ardor he might have nursed for his naive inquisitor. Her Methodist minister father was concerned that her suitor had papist leanings. In 1889 Rudyard Kipling received a letter from a young woman in whom he had evinced an interest, asking him to state his religious beliefs.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)